Choosing tools

- Thank you and goodbye, MS Word

- Choosing editing software, online and offline

- WYSIWYG versus plain text

- Constraints versus creativity

- Open software and standards

So far, we’ve covered a lot of big theory. Now we need some tools for putting that to practice.

Thank you and goodbye, MS Word

The most important step in multi-format editing is to start using something other than MS Word for editing. Pretty much anything else is an improvement. Good software is designed carefully and deliberately for a specific use. MS Word has not been designed as much as assembled by a committee into an usuable monster of terrying proportions.

Choosing editing software, online and offline

There are two main kinds of editing software to choose from, and you may use each one in different contexts: text-only editors, and collaborative editors.

There are also text-only editors that are collaborative! They are rare, though, so it’s generally safe to think of text-only editors and collaborative editors as separate things.

Text-only editing

First, what is text-only editing? Text-only editing is editing in plain-text files. When you do this, you’ll probably be using a particular writing structure called markdown.

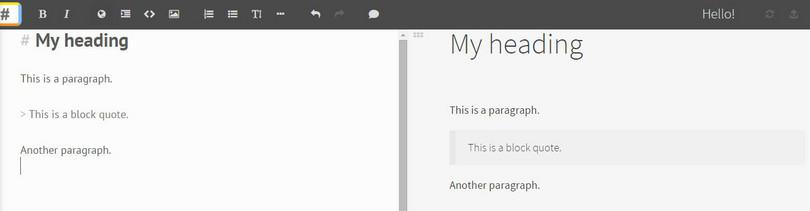

If you’re online, go to Stackedit.io to write some plain-text markdown. Type on the left, and on the right Stackedit turns your plain text into formatted HTML.

On the left, you type plain text in a markdown structure. On the right, you get formatted HTML.

On the left, you type plain text in a markdown structure. On the right, you get formatted HTML.

What we’re seeing here is the separation of content (which is structured text and image-references only) from formatting and design.

What are the big advantages of text-only editing in markdown?

- Smaller, faster files.

- Computers need perfect consistency (the digital age is a wonderful place for obsessive copy editors). Here the tools force our hand, and we learn to be less sloppy.

- Text-only means fewer copy-paste messes (when you copy paste into a new document and the fonts go all weird), because you get only and exactly what you see when you paste: plain text.

- Less file corruption, because there is simply less going on – less code to go wrong.

- Better version control, which we’ll talk about later.

Text-only editors can be online (used in a browser) or offline. Some of the most powerful text-only editors are actually designed for writing software code, like Sublime Text, Atom, Brackets and Visual Studio Code (which can all be used for free).

One of the most powerful features of text editors is regular-expression search-and-replace, or regex. This lets you search and replace patterns of text and not just fixed words.

Collaborative editing

Collaborative editing completely changes the way we write, edit and deliver documents.

What is collaborative editing? In short, you and someone else can edit the same document at the same time online. The most common tool for this is Google Docs.

What are the major pros of collaborative editing?

- It lets others watch while you work. And you can watch while others work. Publishing is weird because it’s always been a team sport played by lonely freelancers from their own home offices. Collaborative editing instantly makes the team aspect real and useful.

- You can use commenting for feedback and discussion. Track changes isn’t the same as actual live annotation. No more emailing documents with increasing repetitions of the word ‘final’ in the file name.

- Instant delivery of work and real-time review. As soon as you’re ready for your colleagues to check something, share the doc and the ball’s in their court. A lot of editing is just problem solving, and collaborative editing means the publisher–editor–designer are basically always in the room together at the same time.

It’s amazing that Google Docs has been around for years and editors are still editing in MS Word.

The one downside of collaborative editors is that you must usually be online to use them.

WYSIWYG versus plain text

Most collaborative editors, like Google Docs, use a ‘WYSIWYG’ view: What You See Is What You Get. WYSIWYG refers to the fact that if you print your document out or send it someone else, it will look the same as when you created it.

The way they do that is by storing the content in code behind the scenes, often in some kind of XML. Most WYSIWYYG editors will not let you see the underlying code: it’s the job of the software to create and maintain that code as you edit. (Some programs do that better than others. MS Word has a notoriously bad underlying code structure, for instance. New software projects like Texture claim to maintain very clean underlying code.)

In technical terms, WYSIWYG editors combine content and design in the same file. This is nice for writing, and bad for book production, because we want to separate content and design. By tempting us to add design flourishes as we write, WYSIWYG editors encourage sloppy thinking, and weakly structured documents.

For instance, to create a heading, many authors and editors will type the heading text as a paragraph, highlight it, and make it big and bold. But a big, bold paragraph is not a heading.

As that document makes its way into production or is processed by machines later on, that heading’s ‘headingness’ might be lost, and the structure of the document will break down. For instance, software that might otherwise create clickable navigation by listing a document’s headings will simply skip that little bold paragraph.

There is no good reason to ask authors to change their writing tools. If an author is most comfortable creating their text in MS Word, that’s fine. But as editors we are concierges: it is our job to translate the author’s intentions into a format that machines can understand.

In traditional Word–InDesign–PDF workflows, good typesetters act as concierges, translating intended structure into actual document structure. In multi-format editing, there is often no typesetter to do this. So editors now bear this responsibility.

Plain-text markdown is one useful way to do this, because markdown forces us to be explicit about things like headings (and blockquotes, italics, links, and more). Alternatively, responsible editors should learn how to use their WYSIWYG editor’s styling functions to ‘tag’ things like headings, so that those elements are correctly marked up in the file’s underlying code.

Constraints versus creativity

As you can tell by now, working with new editing tools means navigating new kinds of constraints on your creativity. Picking the right tool can be about deciding what constraints you want for a given job.

For instance, if you’re doing heavy development editing, you want to be in a creative headspace, not thinking about the technicalities of perfect structure and tagging. Working in Google Docs is probably best, especially if you’re collaborating with others.

But if you’re doing copy editing or implementing proof corrections, it can be far better to work in a plain-text editor, with a monospace font (where all characters have the same width), so that structure and errors are easier to spot, without the distractions of design and formatting.

That is, when you’re creating, you need to use whatever tool feels most natural – to find the shortest distance between your brain and the words. But when you’re preparing a manuscript for production, your brain is focused on structure and accuracy, and markdown comes into its own. Design disappears and you can really control exactly what goes into the text.

Open software and standards

When choosing your tools, you should also consider:

- who creates and owns them, and under what terms

- do they follow common standards, and

- how much do they cost?

Open-source software

Open-source software is software that others can copy and modify without permission from the owner.

Open-source software has had a bad reputation in the past, because most early open software was created by volunteers or academics without much investment of money.

These days, open-source software is important to all of the biggest technology companies in the world, and open-source products are increasingly the best you’ll find.

For organisations, it’s often safest to use good, open tools, because you can’t get locked in with a specific vendor. That said, when evaluating open software, make sure that your choice of tool has a big, strong, happy community behind it. This will mean it will keep getting better, and you’ll be able to find support online easily.

Open standards

Open standards are agreements on how things work. For instance, PDF is an open standard: anyone can read and contribute to the official documents that define how PDFs work, and build PDF software.

That was not always the case. The PDF specification was owned by Adobe for many years, and Adobe charged companies to use it. In a surprising and wonderful move, Adobe made the standard open in 2008. It suited them at that point, too, because they were becoming the premier provider of proprietary software for creating PDFs (with InDesign and Acrobat especially). By making the standard open, they made PDF more important, which made it easier to sell their software. It was a win–win.

For long-term sustainability, look for tools that follow popular open standards. For instance, an editor that stores text as clean HTML is a far safer choice than an editor that stores text in a clever but obscure flavour of XML.

There are standards for almost everything: metadata standards (many of which, like ONIX, are not open), scholarly publishing standards, data standards, textbook standards, accessibility standards, and so on.

You’ll never have time to find and understand them all, but before you make choices about editorial tools and processes, make time to learn what big standards exist in your field.