Part A How Vukuzenzele adds value to informal-settlement upgrading

In this Part A of the User Manual, we provide a high-level overview of the important elements in the project environment of in-situ upgrading, and also provide a value proposition of why Vukuzenzele can support deep and meaningful community participation, which is required by law.

Informal-settlement upgrading is inherently complex, and requires well-considered strategies and tools to secure, motivate and sustain community participation. We have developed an innovative serious game which can help to engage the community and also incorporate their visions for the future of their settlement.

Informal settlements in South Africa

Addressing issues of residential informality is undoubtedly one of the greatest challenges facing cities in the 21st century. Conventional and market-based solutions perpetuate spatially divided cities. This is an exponential problem. An astounding 1.2 billion urban dwellers live in slums. The growth in informal settlements is driven by a global-scale urbanisation from rural to urban areas, and is especially prevalent in countries in the Global South. In 2008, according to the United Nations, we reached a tipping point where, for the first time ever, more than half of the global population lived in cities (i.e. 3.5 billion of 7 billion citizens live in urban areas). By 2024 it is expected that the world population will increase by 1 billion people.

What is an informal settlement?

While national governments interpret the phenomena of residential ‘informality’ in various ways, the commonly accepted definition of an informal settlement is provided by UN Habitat in a report titled The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements (2003).

In this report, a simple definition was adopted as ‘a heavily populated urban area characterised by sub-standard housing and squalor’ and includes any of the five characteristics associated with slums, namely:

- inadequate access to safe water;

- inadequate access to sanitation and other infrastructure;

- poor structural quality of housing;

- overcrowding; and

- insecure residential status.

In South Africa, Statistics South Africa define an informal settlement as ‘an unplanned settlement on land which has not been surveyed or proclaimed as residential, consisting mainly of informal dwellings (shacks)’ where an ‘informal dwelling’ is defined as ‘a makeshift structure not approved by a local authority and not intended as a permanent dwelling’.

– Metadata, Annexure 1: concepts and definitions of Census 2011

Informal-settlement upgrading is squarely on the policy and programme agenda of the government of South Africa, and since at least 2010, institutional capacity has been created to advance the application of the housing programme, Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme (UISP), Part 3 of the National Housing Code. The change in focus is responsive to a problematic situation: demand keeps outstripping housing supply.

‘Slum upgrading remains the most financially and socially appropriate approach to addressing the challenge of existing slums’ (UN Habitat 2014:15).

Since 1994, government has delivered 2.8 million subsidised houses, but informal settlements have grown from 300 in 1994 to 2400 in 2014, and represents nearly 20% or one in five urban households. Government, through its National Development Plan 2030, has acknowledged that informal settlements will remain a persistent component of cities for the foreseeable future, and rather than discriminating against informal dwellers through evictions, relocations and displacements, we should be working towards dignified living spaces through incremental step-by-step upgrading.

The UISP makes it clear that upgrading needs to happen in an empowering and participatory manner, and allocates 3% of the total project funding to the community engagement work required to occur during the pre-planning phases of the project.

Why participation matters

Involving communities in the design, phasing and implementation of an upgrading project is essential. Why? Because without meaningful engagement, consistent communication and collaboration, projects could fail due to direct action resulting in losses of millions of rands due to ceased works. Community protest action, as observed by researchers, is intrinsically linked to poor engagement and service-delivery records, and the process of building trust needs to occur within a well-considered approach.

Did you know?

The majority of community protests, which rose to 1–3 protests per day in 2017/18 according to Africa Check, relate to service delivery and housing issues. This is indicative of the need for officials to address broad-based issues rather than isolated projects that benefit only a few.

– Africa Check 2018 (drawing on Municipal IQ and Institute for Security Studies data)

Participation is also a constitutional right, and is required by law in the UISP and National Housing Code.

A Serious Game: How it came about

ReBlok aims to respond to some of these challenges and received seed funding to develop the serious game Vukuzenzele through the Serious About Games challenge in 2017/18, an initiative of the Western Cape Department of Economic Development and Tourism (DEDAT) with core partners the Cape Innovation and Technology Initiative (CiTi), Interactive Entertainment South Africa (IESA), 67 Games, and the Craft and Design Institute (CDI).

Sixteen teams entered the competition, and four were chosen to develop a prototype and present their playable game to a judging panel including WITS game-design lecturer Hanli Geyser, international game developer Veve Jaffer, start-up consultant Alex Fraser, gaming industry lawyer Nicholas Hall, and Olivia Dyers and Bianca Mpahlaza-Schiff of DEDAT. Vukuzenzele by ReBlok, a collaboration between Renderheads and iKhayalami, was announced as the winner at the finals held at the Bandwidth Barn in Woodstock on 4 April 2017.

‘Serious games are increasingly being used not only in education, but in the health sector and to encourage positive behaviour change. Some of the most successful recent serious games – such as Sea Hero Quest – are also research tools. DEDAT has been visionary in using a serious game to connect with their constituency, and to learn from communities about the decisions people make when considering socio-economic choices.’

— Michelle Matthews, project manager, Cape Innovation and Technology Initiative

For more information: www.seriousaboutgames.co.za

The prototype was further developed and was ready for a launch event in AT Section, Site B, Khayelitsha, in April 2018. This site was finalised after a thorough site-selection process, which we describe in more detail in Part B of this manual. Vukuzenzele shows real promise for serious games to inform project implementation. Indeed, eight months later, after negotiations with the City of Cape Town were concluded, re-blocking commenced in AT Section, largely based on the layout design created by the community through gameplay.

- April 2017

- Vukuzenzele wins Serious About Games competition

- June 2017

- Product development commences

- July 2017

- Community radio announcements for participants in prototype gameplay

- Dec 2017

- Site for gameplay identified as AT Section

- Feb 2018

- Aerial mapping via drone and photogrammetry

- April 2018

- Game launch in AT Section, Khayelitsha

- November 2018

- Reblocking of AT Section by iKhayalami begins

Re-blocking is an intervention in settlement upgrading currently being implemented by iKhayalami. Re-blocking is an approach to a design and implementation process that is driven by the community and involves the reconfiguration of a settlement layout into one that is more rationalised allowing for the creation of demarcated pathways or roads, public and semi-private spaces, increased access for emergency vehicles, and the provision of infrastructure and basic services (e.g. ground compaction, water and sanitation, community facilities).

‘We need to make sure we play a role in driving the digital revolution. Through mechanisms like Serious About Games we are claiming our space in this new world economy. More importantly, we are harnessing the power of technology to help residents improve their lives.’

– Western Cape Government, then-Minister of Economic Opportunities Alan Winde at the Serious About Games launch event, April 2017

Re-blocking: Building a game on ten years of practical experience

iKhayalami, meaning ‘my home’ in isiXhosa, was established in 2006 after founder Andy Bolnick researched international best practice and developed solutions to upgrade settlements in a rapid turnaround process. This was and remains highly innovative, considering the burdensome and long delays in conventional government-led upgrading processes.

In these re-blocking projects, iKhayalami has formed close working relationships with community networks, notably the South African affiliate to Shack Dwellers International: the Federation of the Urban Poor (FEDUP) and Informal Settlement Network (ISN).

As a founding partner of ReBlok, iKhayalami has incorporated more than a decade of experience in the game design, executed by Renderheads. Please refer to the following case studies on www.ikhayalami.org/projects.

| Project | Location | Dates | Status (with NGO and community Partners) |

Households upgraded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joe Slovo | Langa, Cape Town | 2009–2011 | Completed | 250 structures |

| Sheffield Road | Philippi, Cape Town | 2010–2012 | Completed | 110 structures |

| Ruimsig | Johannesburg | 2011–2012 | Completed | 98 structures |

| Mtshini Wam | Milnerton, Cape Town | 2012–2013 | Completed | 250 structures |

| BM Section | Khayelitsha, Cape Town | 2013 | Completed | 450 structures |

| OR Tambo TRA | Khayelitsha, Cape Town | 2013 | Completed | 90 structures |

| Flamingo Crescent [WF9] | Wetton, Cape Town | 2014 | Completed | 104 structures |

| BT Section Empower shack | Khayelitsha, Cape Town | 2015–2018 | Under construction | 72 structures |

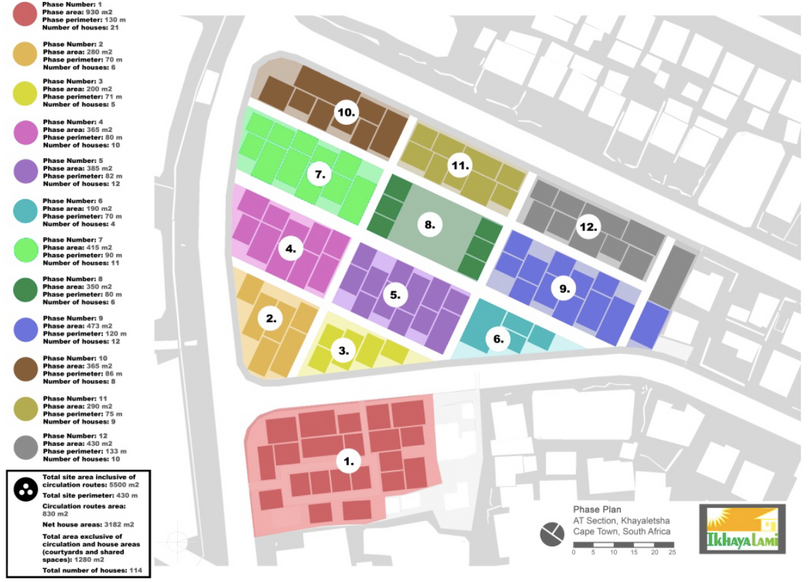

| AT Section | Khayelitsha, Cape Town | 2018 | Under construction | 114 structures |

Based on these case studies, the following lessons from re-blocking projects have been incorporated in advising communities, government and private-sector service providers in in-situ upgrading techniques.

- Reblocking builds community capacity in leadership structures, data collection, project management and reporting, which are useful skills to engage in longer-term projects.

- The project results in rationalised space for ease of movement, public spaces, community courtyards and passive surveillance.

- The project also results in security of tenure. In some projects, the post office has officially recognised the new streets and allocated postal addresses to residents.

- When individuals agree to contribute their savings towards the upgrade, communities tend to take greater ownership of the development process.

- The project environment creates partnerships between residents, government and other partners in development.

Re-blocking AT Section: Vukuzenzele in action

ReBlok’s intention with Vukuzenzele was always to test the application of gameplay and how it results in implementation. While the alpha version of the game was being completed, iKhayalami engaged communities and applied its re-blocking readiness matrix to several potential sites. Residents were invited to participate in the game by sending a message via WhatsApp including their name, area, and settlement name.

Once AT Section in Site B, Khayelitsha, was selected as a pilot case with community support, iKhayalami entered into negotiations with the City of Cape Town. A drone flyover and enumeration took place in order to render a settlement-identical gamelayer in Vukuzenzele.

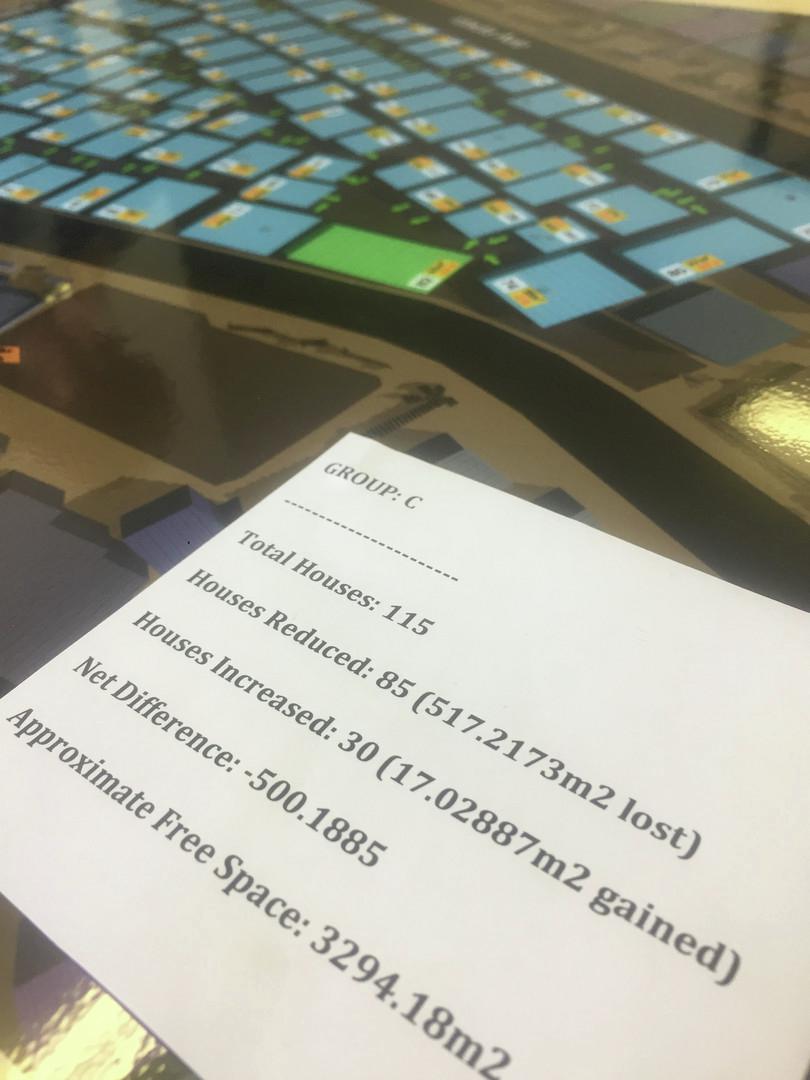

In AT Section, ReBlok worked with community leaders to form several teams of 3–6 resident players, who competed for three cash prizes to the total value of R25 000. The game – installed as a large touchscreen tabletop – was housed in a local school and teams solved the layout over several weeks.

Timeline of the site selection and stakeholder engagement process:

- July 2017

- Provisional site assessment through aerial imaging

- 31 July 2017

- Radio announcement for community expression of interest

- August–September 2017

- Scoping out sites

- September–October 2017

- Preliminary settlement engagement

- October–November 2017

- Matrix data collection

- 27 November 2017

- iKhayalami and community organisers finalise recommendation

- 4 December 2017

- iKhayalami, Better Living Challenge (CDI), DEDAT select site

- February 2018

- Aerial mapping via drone and photogrammetry for game level

- April 2018

- Vukuzenzele game installed at local school

- April–May 2018

- Vukuzenzele gameplay completed by 8 teams

- May 2018

- Community engagement on preferred designs by teams

- 29 May 2018

- Final adjudication of community designs by DEDAT, CiTi, ReBlok

- June 2018–Feb 2019

- Refining of final design and implementation plan, with input from local government partners

- August 2018 (ongoing)

- Project implementation

Incorporating Vukuzenzele: The UISP project cycle

On participation, the UISP recognises the central role of communities and provides for opportunities to incorporate their ‘deep-rooted knowledge’ to the project planning and ‘this knowledge must be harnessed to ensure that a township design and services standards as well as the housing solutions and the economic and social facilities opted for, are targeted at satisfying the actual needs and preferences’ (UISP 2009:30).

One of the key avenues for financing community participation is therefore the terms of reference (ToR) local governments compile to procure the services to upgrade an informal settlement. Typically, engineering companies tender for this work because they are often best suited to deal with the more expensive infrastructure development components. By drafting the ToR, local governments can insist on a minimum required level of community participation, and to this effect, 3% of the overall project budget is ring-fenced for community participation activities, and 8% to overall project management.

Policy Summary: The UISP, or Part 3 of the National Housing Code

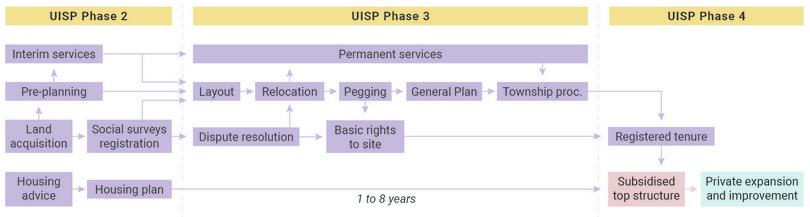

The UISP provides funding over three phases, after which (in Phase 4) qualifying beneficiaries can apply for housing construction and ownership assistance. In the three phases leading up to housing development, there are therefore certain deliverables that need to be achieved, and Vukuzenzele game can be best applied in Phase 1, or the pre-planning stage. This is a long process (up to 8 years) and investing upfront in community participation could sustain a longer engagement through a project steering committee.

Phase 1 provides for pre-planning and project preparation and includes activities such as preliminary planning, geotechnical investigation, land acquisition and a range of community facilitation services, such as conflict resolution, socio-economic surveying, and housing support services and information sharing.

In Phase 2, interim services such as water, sanitation, refuse removal and electrification are provided, while settlement planning commences. This includes detailed town planning, land surveying and pegging, contour surveying and civil engineering design. The UISP emphasises the provision of social and economic amenities, for which municipalities can apply for funding from the Social and Economic Amenities Programme, although funding from municipal budgets should be the first option.

During Phase 3, full services are provided including land rehabilitation, final environmental impact assessment, project enrolment with the National Home Builders Registration Council, and project management and professional fees.

Not all projects follow the UISP project cycle, however. For example, re-blocking relies on government allocating discretionary grants such as the Urban Settlement Development Grant to deliver basic services, and iKhayalami has been fundraising to heavily subsidise the building materials required for new top structures. Government departments can also procure the upgrading of informal settlements through the following grants received from national government:

-

Urban Settlement Development Grant (USDG): A grant for capital investment in order to support the national human settlements development programme focusing on poor households.

-

Human Settlements Development Grant (HSDG): Capital funding for the creation of sustainable human settlements (via provincial departments of human settlements spread across the province).

-

Municipal Infrastructure Grant (MIG). The MIG is demand-driven and relies on municipalities to coordinate the planning of expenditure. All funding allocations are linked to the IDP, and community participation in identifying projects needs to be proven. The Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (COGTA) coordinates the grant nationally through the MIG Unit. There are three categories in MIG funding:

- households,

- public municipal facilities, and

- institutions other than public municipal facilities.

Funding participatory planning in upgrading projects

Earlier we indicated that the finance sources for informal settlement upgrading are diverse, but taking a cue from the official UISP, we are able to formulate a value proposition for contractors’ engagement with government on service-level agreements.

In Phase 1, the project pre-planning and project-preparation phase, approximately 3% of the overall project budget is reserved for social-facilitation services. These services include the following, based on the policy guidelines:

- socio-economic surveying of households

- facilitating community participation

- project information sharing and progress reporting

- conflict resolution, where applicable

- training and education on housing rights and obligations

- capacity building of housing beneficiaries

- assistance with the selection of housing options

- management of building materials

- relocation assistance.

‘The key objective of this programme is to facilitate the structured in situ upgrading of informal settlements as opposed to relocation (page 13) […] Responsible authorities should adhere to the principle that community participation is the key to success and that relocation of communities should be a last resort (page 25).’

Part 3 of the National Housing Code (2009), Upgrading of Informal Settlements Programme

ReBlok can add value to any team embarking on an informal-settlement upgrading project. By calculating the subsidy quantum (2018 figures), the potential budget available to participatory planning is presented. Consider three types of informal settlement upgrading contexts:

| Small | Medium | Large | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of households | 500 households | 1500 households | 3500 households |

| Potential budget available during Phase 1 | R640 500 | R1 921 500 | R4 483 500 |

| Total project budget | R19 million | R57 million | R134 million |

Getting started with ReBlok

ReBlok can add value to a wide variety of built-environment professionals tendering for such work, including project managers, engineers, planners, architects and surveyors. We can also support in the following value-adding services we provide:

- site identification criteria and engagements with the local government

- aerial surveillance with drone and photogrammetry software

- creation of a settlement CAD model and the rental of game hardware

- community data gathering through household-level enumeration and data collection

- training and development of skilled community facilitation to ensure that public participation processes are deep and meaningful.